Lesson 4: OOP - Objects, Classes & Constructor

Goals

- Know what Object-Oriented Programming is.

- Be able to translate a real-life object to a programming object.

- Be able to create a Java class.

- Be able to instantiate an object of a Java class.

- Understand the difference between a class and an instance.

- Have an overview about class constructors.

- Have an overview about the main concepts of OOP.

Recap & Assignment check

Let’s look into the assignment from lesson 3

What Is an Object?

An object is a software bundle of related property and behavior. Software objects are often used to model the real-world objects that you find in everyday life. This lesson explains how property and behavior are represented within an object, introduces the concept of data encapsulation, and explains the benefits of designing your software in this manner.

Objects are key to understanding object-oriented technology. Look around right now and you’ll find many examples of real-world objects: your dog, your desk, your television set, your bicycle.

Real-world objects share two characteristics: They all have property and behavior. Dogs have property (name, color, breed, hungry) and behavior (barking, fetching, wagging tail). Bicycles also have property (current gear, current speed) and behavior (changing gear, applying brakes). Identifying the property and behavior for real-world objects is a great way to begin thinking in terms of object-oriented programming.

Take a minute right now to observe the real-world objects that are in your immediate area. For each object that you see, ask yourself two questions: “What possible properties can this object be in?” and “What possible behavior can this object perform?”. Make sure to write down your observations. As you do, you’ll notice that real-world objects vary in complexity; your desktop lamp may have only two possible properties (on and off) and two possible behaviors (turn on, turn off), but your desktop radio might have additional properties (on, off, current volume, current station) and behavior (turn on, turn off, increase volume, decrease volume, seek, scan, and tune). You may also notice that some objects, in turn, will also contain other objects. These real-world observations all translate into the world of object-oriented programming.

Software objects are conceptually similar to real-world objects: they too consist of property and related behavior. An object stores its property in fields (variables in some programming languages) and exposes its behavior through methods (functions in some programming languages). Methods operate on an object’s internal property and serve as the primary mechanism for object-to-object communication. Hiding internal property and requiring all interaction to be performed through an object’s methods is known as data encapsulation — a fundamental principle of object-oriented programming.

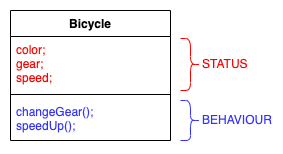

An example: a Bicycle Object

Consider a bicycle, for example:

Any bicycle you see on the street can be represented through an object; its status is represented by their properties:

- color

- gear

- speed

part of the status does change over time due to object behaviors, which are represented by its methods:

- changeGear()

- speedUp()

We will represent the bicycle object like this

What Is a Class?

A class is a blueprint or prototype from which objects are created. This section defines a class that models the property and behavior of a real-world object. It intentionally focuses on the basics, showing how even a simple class can cleanly model property and behavior.

In the real world, you’ll often find many individual objects of the same kind. There may be thousands of other bicycles in existence, all of the same make and model. Each bicycle was built from the same set of blueprints and therefore contains the same components. In object-oriented terms, we say that your bicycle is an instance of the class of objects known as bicycles. A class is the blueprint from which individual objects are created.

The following Bicycle class is one possible implementation of a bicycle class:

class Bicycle {

String color = "green";

int speed = 0;

int gear = 1;

void changeGear(int newValue) {

gear = newValue;

}

void speedUp(int increment) {

speed = speed + increment;

}

void printProperties() {

System.out.println("color:" + speed + "speed:" + speed + " gear:" + gear);

}

}

The syntax of the Java programming language will look new to you, but the design of this class is based on the previous discussion of bicycle objects. The fields speed, and gear represent the object’s property, and the methods (changeGear, speedUp) define its interaction with the outside world.

Objects are instances of a class

You may have noticed that the Bicycle class does not contain a main method. That’s because it’s not a complete

application; it’s just the blueprint for bicycles that might be used in an application. The responsibility of creating

and using new Bicycle objects belongs to some other class in your application.

Here’s a BicycleDemo class that creates two separate Bicycle objects and invokes their methods:

class BicycleDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create two different

// Bicycle objects

Bicycle greenBike = new Bicycle();

Bicycle redBike = new Bicycle();

// Invoke methods on

// those objects

greenBike.speedUp(10);

greenBike.changeGear(2);

greenBike.printProperties();

redBike.color("red");

redBike.speedUp(10);

redBike.changeGear(2);

redBike.speedUp(10);

redBike.changeGear(3);

redBike.printProperties();

}

}

The output of this test prints the current speed, and gear for the two bicycles:

color:green speed:10 gear:2

color:red speed:20 gear:3

Constructors

A class contains constructors that are invoked to create objects from the class blueprint. Constructor declarations look

like method declarations—except that they use the name of the class and have no return type. For example, Bicycle has

the following constructors:

class Bicycle {

/** Properties */

String color;

int speed;

int gear;

/** Constructors */

public Bicycle(String color, int startSpeed, int startGear){

this.color=color;

this.gear=startGear;

this.speed=startSpeed;

}

public Bicycle(){

this.color="green";

this.gear=1;

this.speed=0;

}

/** Methods */

void changeGear(int newValue) {

gear = newValue;

}

void speedUp(int increment) {

speed = speed + increment;

}

void printProperties() {

System.out.println("color" + color + "speed:" + speed + " gear:" + gear);

}

}

To create a new Bicycle object called blueBike, a constructor is called by the new operator:

Bicycle blueBike=new Bicycle("blue",0,8);

Bicycle yourBike = new Bicycle(); invokes the no-argument constructor to create a new Bicycle object

called yourBike.

Bicycle yourBike=new Bicycle();

yourBike.gear=5;

yourBike.speed=2;

Both constructors could have been declared in Bicycle because they have different argument lists. As with methods, the Java platform differentiates constructors on the basis of the number of arguments in the list and their types. You cannot write two constructors that have the same number and type of arguments for the same class, because the platform would not be able to tell them apart. Doing so causes a compile-time error.

You don’t have to provide any constructors for your class, but you must be careful when doing this. The compiler automatically provides a no-argument, default constructor for any class without constructors.

OOP benefits

In contrast to other styles of programming (e.g procedural, functional, and so on) Object Oriented Programming assumes that everything can be represented as an object. Interaction between defined objects defines the applications.

We will use the Bicycle example to introduce the benefits of this approach:

-

Modularity: The source code for an object can be written and maintained independently of the source code for other objects. Once created, an object can be easily passed around inside the system.

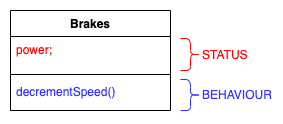

Given that everything is representable as an object, object can be compounded of other objects. We can identify an object for our bicycle brakes

This is then the Brakes Class

class Brakes { int power = 2; int decrementSpeed(int initialSpeed) { int finalSpeed = initialSpeed - power; return finalSpeed; } }so we can enhance our Bicycle Class using the Brakes Class:

class Bicycle { /** Properties */ String color; int speed; int gear; Brakes brakes; /** Constructors */ public Bicycle(int color, int startSpeed, int startGear){ this.color=color this.gear=startGear; this.speed=startSpeed; this.brakes=new Brakes(); } public Bicycle(){ this.color="green"; this.gear=1; this.speed=0; this.brakes=new Brakes(); } /** Methods */ void changeGear(int newValue) { gear = newValue; } void speedUp(int increment) { speed = speed + increment; } void hitBrakes() { speed = brakes.decrementSpeed(speed) } void printProperties() { System.out.println("color:" + color + "speed:" + speed + " gear:" + gear); } } -

Information-hiding: By interacting only with an object’s methods, the details of its internal implementation remain hidden from the outside world.

Just imagine our Brakes class to be implemented as follows:

class Brakes { int power = 2; int decrementSpeed(int initialSpeed) { int finalSpeed = initialSpeed / power; //here we divide speed by the power! return finalSpeed; } }The internal implementation of

decrementSpeed()changed, but it has no implication to its usage in Bicycle class. -

Code re-use: If an object already exists (perhaps written by another software developer), you can use that object in your program. This allows specialists to implement/test/debug complex, task-specific objects, which you can then trust to run in your own code.

Lots of manufacturers out there have their implementation of Brakes

V-BRAKES DISC-BRAKES COASTER BRAKES

import shimano.VBrakes; class Bicycle { /** Properties */ String color = "green"; int speed = 0; int gear = 1; VBrakes brakes; }

-

Pluggability and debugging ease: If a particular object turns out to be problematic, you can simply remove it from your application and plug in a different object as its replacement. This is analogous to fixing mechanical problems in the real world. If a bolt breaks, you replace it, not the entire machine.

Which means: if you prefer the disc-Brakes, you can use them

import brembo.DiscBrakes; class Bicycle { /** Properties */ String color = "green"; int speed = 0; int gear = 1; DiscBrakes brakes; }

We will learn more advanced techniques on how to make VBrakes and DiscBrakes interchangeable with no changes in the Bicycle class, by using interfaces and/or the

extendsdirective.

Exercise & Assignment

Follow the link and download the assignment from GitHub Classroom

Materials

- Object-Oriented Programming Concepts by Oracle

- Providing Constructors for Your Classes

- OOP: Everything you need to know about Object Oriented Programming

- 4 Pillars for Object Oriented Programming